Eleven years have passed since my father passed, and the changing role that grief plays in my relationship with him has become a part of the longer narrative of who I am because of him. There are no new pictures of him. No recent conversations. No social media updates. He’s frozen in time along with the moments, the lessons, and the images which aren’t quite as clear as they once were.

One of my most stubborn habits remains. Every summer, around this time, I start checking the Dodgers' baseball standings on an increasingly frequent basis. My mind then immediately asks itself if I should call my Dad to get a sense of where our beloved team stands. This happens a few times a week, and my feelings immediately run the gamut from sadness and loss to nostalgia and a happy yet still discomfited contentment that my Dad is still there with me, checking the Dodgers box scores through another season of life.

Like many fathers and sons, baseball was, and is, a timeless bond between us that began from my earliest memories of him and remains more than a decade after he’s been gone.

So it was that I found myself thinking about Dad this past Father’s Day. A particularly reflective one for me as my own adult children, busy with their own careers and young adult lives, have transitioned to phone calls and texts wishing their Dad a Happy Father’s Day. We’ve transitioned to the stage where those messages are as meaningful as any gift, and I’m just grateful that they’re healthy, happy, and remember. The same thing my father would tell me in my same phase of life.

As a boy, there wasn’t a single Father’s Day during my own Dad’s life where my gift wasn’t about the Dodgers - tickets to a game, a baseball card of his boyhood hero and Brooklyn Dodger first baseman Gil Hodges, a framed photo of the famed Boys of Summer in 1955. Always, the Dodgers were there. Always.

Perhaps it was coincidence or maybe spiritual intervention that on this last Father’s Day Sunday, I realized I had a stop on my book tour in Albuquerque, New Mexico, the coming week. The Madrid surname is one of the few Hispanic last names whose origins run through the New Mexico territory, and I thought that if I had some time, I’d research some spots where the Madrid name clustered prominently. If time permitted, I’d rent a car and poke around the areas around where I’d be speaking and signing books. If I found a neighborhood of Madrid names in my internet search, I could spend a morning or afternoon driving through the New Mexican desert and maybe get within a stone’s throw of a distant relative whose life could have been my own if my grandfather had never left the state. It seemed like a good way to rekindle some memories and think about my father and our family’s origin story. Besides, when would I ever be in Albuquerque again?

It all started with the most sincere of intentions. Nothing more than a good way to spend some time thinking about my Dad and refreshing the memory bank that time, that thief was increasingly taking away from us.

The Madrid family has deep roots in the harsh, red, arid New Mexico soil, our surname appearing on census records and land grants like breadcrumbs leading back through generations. But it was the discovery of an actual town named Madrid, fifty miles north of Albuquerque, that transformed my casual genealogical curiosity into something approaching obsession. What began as a simple desire to connect with my family heritage during a Father’s Day weekend became a journey into the liminal space between memory and myth, between the stories we tell ourselves and the truths we can never quite grasp.

This small desert town that shares my name began to slowly seduce me into a string of coincidences that I could not ignore.

Madrid, New Mexico, exists in that peculiar American category of places that refuse to stay dead. Founded sometime between 1869 and 1879—depending on which version of history you trust—the town embodies the slippery nature of truth itself. Even its name carries dispute: named for the Spanish capital, or perhaps for the Madrid family who owned coal claims in the area. While this dispute may accurately sound like different roads to the same answer, any Madrid can tell you that those different roads matter far more than the destination. The famous Madrid name of Spanish royalty is not the same as the accomplished Madrid name of the New World. Even the pronunciation matters. In New Mexico, it is pronounced MAD-rid, while those of us assimilated in California culture pronounce it ma-DRID.

The uncertainty of Madrid’s origin story feels familiar, like trying to reconstruct conversations with my father eleven years after his death, when the details blur but the emotional resonance remains sharp.

The town’s rise and fall read like a compressed American dream. Coal discovered in the surrounding hills transformed Madrid from a collection of mining claims into a company town that, at its peak in the 1920s and 1930s, boasted 3,000 residents, bigger than Albuquerque at the time. Madrid also had a tenuous, if exaggerated, relationship with two American icons - Thomas Edison and Walt Disney. These icons found inspiration in Madrid, where the vision of one would build off the vision of the other..

The Albuquerque and Cerrillos Coal Company that brought these thousands of people to an isolated patch of sand and strife didn’t just extract carbon from the earth—they built a world. Company houses lined dirt streets, the company store extended credit against future wages, and miners descended into the underworld darkness each day with the faith that the town above would still be there when they emerged.

The abundant coal provided free electricity for its coal mining employees/residents, and it began a tradition of lighting up its Main Street in the 1920s. This was an extraordinarily ambitious and novel project for the time and reportedly drew the interest of Thomas Alva Edison, the wizard of Melo Park, himself to head west where he would personally consult on the project. The project was a remarkable success. So much so that it is rumored that so bright were the lighted Christmas displays that Pan-Am would route planes flying over the area over Madrid so that their nighttime passengers could marvel at the city of lights breaking through the dark desert landscape.

So notorious did Madrid become for its extravagant displays of light bulbs and dangling cords elegantly strewn across city streets that Walt Disney himself visited the city three times. It was Madrid that inspired Main Street in Disneyland, as local lore goes.

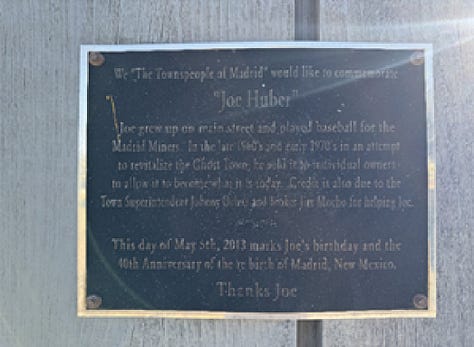

Oscar Huber, the company’s general manager and town superintendent, understood that his prospering town needed more than work to survive—it needed dreams. In part to prevent the unionization of the coal miners, Huber provided his employees two things - a still to produce liquor during prohibition and world-class entertainment for the time: Baseball.

In the mid-1930s, he commissioned the construction of a proper baseball stadium, complete with grandstand and eventually stone-masoned dugouts, funded by the Depression era WPA (Works Progress Administration).

He recruited professional players for an AA team and named the team the Madrid Miners, naturally.

But Oscar Huber’s vision went beyond the typical company town amenities and far beyond the infrastructure of minor league ballparks sprouting up around the country in that era. Madrid’s baseball field featured something almost unheard of in Depression-era America: electric lighting for night games. The same coal-fueled electricity that brought fame to the city for its Christmas lights display in the winter could be used to light up a baseball diamond in the summer.

This wasn’t mere extravagance—it was a direct result of Madrid’s unique blessings. The abundance of coal that fed the company’s operations also powered the town’s electrical plant, allowing Madrid to provide free electricity to its residents and, by extension, to illuminate their beloved baseball team’s evening performances under the New Mexico stars. Madrid had the only lighted baseball stadium west of the Mississippi and one of a handful in the country.

The lighted field transformed Madrid into something approaching magical on game nights. While most of America’s small towns played their baseball in the afternoon shadows, Madrid’s miners could emerge from their shifts, wash the coal dust from their faces, and gather under electric lights to watch their team play nine innings late into the desert evening. The Madrid Miners weren’t just a company team—they were a symbol of what prosperity could build, what modern technology could provide, what a community could become when coal flowed freely and electricity cost nothing. The town’s population would double for night games to 6,000 attendees, with the overflows from the grandstands pouring out into surrounding hillsides. Fans from the entire region of New Mexico would gather and park their Ford Model Ts and watch the game from their automobiles. The baseball stadium was a modern spectacle and a point of state pride.

There was also no possible way that some of my relatives had not been among those in attendance. Impossible for a Madrid uncle far removed or a second cousin not to have attended a Madrid Miners game.

That sincere intention that began with a simple search to connect with my father’s past had become a rabbit hole obsession that demanded I reconfigure my trip. By this time, I had stayed up all night researching obscure regional blogs, baseball archives, and chasing ghosts across the distant shadows and far corners of the Land of Enchantment.

My book stop for “The Latino Century” in Albuquerque had rapidly evolved into something more—a pilgrimage. Somewhere in the sprawling geography of Santa Fe County, where my family name was scattered like seeds across the high desert, I found myself planning a detour that felt less like tourism and more like some archaeology of a yearning heart.

I pushed further into the city’s past, watching the concentric circles that connected me with my father begin to converge into a roadmap to place on the map where I could see him and feel him, if only in spirit, one more time.

But coal towns, like our own mortal coils, are built on finite resources, and I learned that by the 1950s, Madrid was dying. The price of coal collapsed, and where Madrid had prospered during the Great Depression, it went bankrupt during the country’s prosperous 1950s. Natural gas was quickly replacing coal. The mines closed, residents left the town seeking better opportunities, and what remained was the architecture of abandonment—empty houses, a silent company store, and the kind of profound quiet that only follows the departure of human voices, children playing, and an empty ballpark. The crack of the bat was replaced by the soft sounds of desert birds that made homes in the dilapidating dugouts. The stadium was overgrown with weeds as its uniformed heroes left for other diamonds. The Albuquerque and Cerillo coal company listed the entire empty town for sale in the Wall Street Journal for the reasonable price of $250,000.

There were no takers.

The grandstand fell into disrepair, and the ballpark was forgotten. Madrid became a ghost town in the most literal sense, a place where the past lingered like smoke in still air. Shuttered abandoned homes that sheltered thousands now stood empty. The population in the 1960s showed that all of its residents were completely gone.

Nothing remained of Madrid but echoes, shadows, and memories.

Yet ghost towns, like the memories of loved ones lost, have a stubborn persistence. In the 1970s, artists and craftspeople began filtering into Madrid’s empty buildings, drawn by cheap rent and the romance of resurrection. They slowly transformed mining shacks into galleries, the old company trading post into a general store selling turquoise jewelry and locally made pottery. Madrid acquired a second life, this one built not on extraction but on creation, not on the darkness below ground but on the desert light above it. The younger, vibrant Madrid had faded with its memories of glory into the past, but it wasn’t completely gone either. Most of what kept it alive were the fuzzy memories of a storied past.

That and the kind of community cohesion and commitment that only shared hardship can forge

It was in researching this cycle of life, death, and resurrection that I stumbled upon the legend that would consume my preparations for my coming trip. It was by far the greatest sign that my father was guiding me to Madrid.

It was the story of one single baseball game played on Oscar Huber’s field. But it wasn’t just any game. It was a game that has become ensconced in Madrid lore like a slab of granite in the New Mexican desert floor. It was the game played between the Madrid Miners and the Brooklyn Dodgers.

The story of the Brooklyn Dodgers playing an exhibition game against the Madrid Miners sometime in May of 1934 appears on a multitude of historical records, travel sites, and personal blogs about the city. The details varied depending on the source—if they could be called sources at all. Some versions place the game later that year, but most of the local mythology stands firm that the game was played in the spring of 1934. Most claimed it was a full nine-inning affair that the Brooklyn Dodgers went on to win; others suggested it was merely batting practice. But every version agreed on the central narrative: Major League Baseball had come to this remote coal camp, and for one afternoon, Madrid had hosted greatness and been the center of the baseball world.

It was, of course, just an exhibition game - if there had been a game at all. But, if true, it would also mean that the Dodgers had played a baseball game west of the Mississippi long before Branch Rickey moved the team west. More importantly, it meant the Dodgers played the first game in the west in a town named Madrid.

My father would have been enchanted by this story, but not as a Brooklyn heartbreak case, as a Los Angeles dreamer. My father had gone to see the Dodgers play that first year in the Los Angeles Coliseum with his father as a boy. Born in Los Angeles in 1946 to parents who had already made their westward journey, he came of age just as his city was preparing to welcome the Dodgers home.

My grandfather Manuel Madrid had left the harsh desert environs of New Mexico over a decade earlier, drawn west by the same promise of opportunity that would later attract major league baseball. By 1930, Manuel’s name appeared on the Los Angeles census alongside his wife Betty, where he scratched out a living as a car mechanic among the sprouting car dealership lots that were multiplying across the Los Angeles basin like desert wildflowers after rain.

When my father was nine years old in 1955, he would spend afternoons playing stickball and listening to Vin Scully’s radio broadcasts of the Dodgers finally beating the Yankees to win their first and only World Series while still in Brooklyn. Upon the announcement shortly thereafter that the Dodgers would be moving to Los Angeles, he wasn’t mourning with Ebbets Field faithful—he was waiting with the anticipation of a child who had been promised something wonderful. The announcement of the Dodgers’ move to Los Angeles after the 1957 season wasn’t betrayal for him; it was validation, proof that his city was finally ready to join the major leagues in every sense. No Major League Baseball team had ever played west of the Mississippi.

Or had they?

The symmetry is almost too perfect: the Madrid family had moved west from New Mexico seeking opportunity, just as the Dodgers would abandon Brooklyn for the promise of California. My grandfather Manuel, working with his hands to build a life among the car lots and orange groves of Los Angeles, was part of the same great migration that would eventually bring Sandy Koufax, Gil Hodges, and Duke Snider to Chavez Ravine. When the Dodgers won the World Series in 1959, 1963, 1965, 1981, and 1988, each victory felt like vindication not just of the team’s westward move, but of every family’s decision to chase dreams across the continent-or, for the Madrids, across the desert southwest.

The possibility that his beloved Dodgers had once played in a New Mexico mining town—a place that shared my family name—felt like the universe offering me a gift wrapped in coincidence. Here was a story that connected my father’s passion to my family heritage, his memory calling me to pilgrimage. I was being given the gift of one more baseball adventure with him. The gift of one more Dodger game. A forgotten game that we could rediscover together.

The fact that the Madrid Miners were the Dodgers’ Double-A farm team only deepened the symmetry. This wasn’t just about major league baseball slumming in the desert; this was about our own family’s story of the romance of baseball and the Dodgers organization, the extended family of my father’s devotion. A deep devotion second only to the Catholic Church.

The more hours I spent on the internet researching this game, the more fantastical the coincidences would become. The storied Hall of Fame manager Casey Stengel would have been there, as would Johnny VanderMeer, the Brooklyn Ace. I began to research Madrid family lineage to get some sense of who in my family tree might have been there watching the Brooklyn Dodgers play the first night game in the western United States in a city named Madrid!

But as I dug deeper into the legend, the story began to dissolve like a desert mirage. No photographs existed of the game. No newspaper accounts from Albuquerque or Santa Fe mentioned it. The Baseball Hall of Fame had no record of any Brooklyn Dodgers exhibition games in New Mexico during the relevant years. The more I searched for evidence, the more the story revealed itself as likely nothing more than oral tradition, passed down through generations of Madrid residents and baseball enthusiasts like a sacred text whose authenticity mattered less to them than its meaning.

This absence of evidence didn’t diminish my fascination—it intensified it. Here was a story that existed in the same liminal space as my memories of my father, real in its emotional impact but impossible to verify through external sources. Like the conversations I remember having with him, growing hazier over time, that may have been composed of multiple interactions compressed into single vivid scenes, or the lessons I attribute to him that might have been learned through observation rather than direct instruction. The Madrid Dodgers game began to occupy the territory between fact and feeling, where family mythology thrives.

And then, deep in my research, I discovered something that transformed speculation into purpose: I discovered that the old baseball stadium still exists. After years of abandonment, decades of overgrown weeds and desert reclamation, the stadium—like some forgotten ancient cathedral—had somehow endured. The grandstand may have weathered and the stone dugouts may have cracked, but perhaps emboldened by the memories of joy and screaming fans it once housed, this centerpiece of a long-forgotten gathering place had refused to surrender entirely to time and elements.

The discovery felt like an archaeological revelation. Here was physical proof that Madrid’s baseball dreams had been real, that the lighted field where miners gathered after their shifts had existed, that the infrastructure for legendary games—mythical or not—remained embedded in the desert landscape like ancient ruins waiting for rediscovery. The ruins of an old stadium would be just enough evidence that this game could have happened, and for a storied past, that just might be enough.

At this point, all the signs were pointing me towards finding Madrid. Somewhere in the New Mexico desert stood the ruins of a baseball cathedral where, if the legend held any truth, the Madrids had first watched the Dodgers play. The mythical game suddenly felt less mythical and more inevitable—of course my relatives would have been there, of course they would have witnessed major league baseball under those electric lights, of course this moment of intersection between my family’s history and my father’s passion - our strongest connection to each other - would have taken place on ground that still existed, still waited to be visited.

I had no choice but to make the journey.

The stadium’s persistence across decades of abandonment felt like an invitation, a suggestion that some stories are too important to let disappear completely, that some places hold their significance even when the world moves on. Whether the Brooklyn Dodgers had actually played there became secondary to the fact that they could have, that the stage for such magic remained set, waiting for someone to remember why it mattered.

The more I considered it, the more the legend seemed to reflect the nature of grief itself. Eleven years after my father’s death, his presence in my life exists primarily now through stories—some verified by photographs or witnesses, others existing only in the unreliable theater of my own aging memory. The specific details matter less than the essential truth they carry: that he was here, that he mattered, that his influence continues to shape my understanding of the world. That is why I am the man that I am.

Madrid, New Mexico, exists in this same space of contested reality. Its incorporation date shifts depending on the source consulted. Its naming remains disputed. Even its current population is uncertain—somewhere between 150 and 400 people, depending on how you count, who you count, and when you ask. But the uncertainty doesn’t make Madrid less real; it makes it more human, more representative of how communities function and persist and remember themselves.

The Brooklyn Dodgers exhibition game, whether it happened or not, serves a similar function in Madrid’s collective memory. It transforms a remote mining town into a place where history paused, if only for a day, where the national pastime intersected with local pride, where something larger than daily survival took place. The story provides Madrid with what every community needs: a narrative that elevates the ordinary into the mythic, that suggests their small corner of the world once mattered to someone beyond its borders.

As I finalized my travel plans, I realized that the truth or falsehood of that fabled Dodgers game had become irrelevant to my pilgrimage. What mattered was that the story existed, that it connected my father’s passion and story to me and my children and to a place that carried my family name, that it offered me a reason to venture beyond the book tour that had brought me to New Mexico in the first place. Sometimes the stories we tell ourselves matter more than the facts we can verify, and sometimes chasing ghosts gives them the signal to lead us to exactly where they know we need to go.

The high desert of New Mexico, like the landscape of memory, is full of places that exist between presence and absence, between what was and what might have been. Madrid sits among them like a question mark made of adobe and ambition, a reminder that the most important truths often can’t be documented or verified—only experienced, only felt, only carried forward in the stories we choose to keep alive.

While driving north from Albuquerque, I travelled not just toward a ghost town that refused to stay dead, but toward the place where my father’s love of baseball intersects with my family’s history, where legend meets longing, where the possibility of connection transcends the limitations of proof. In the end, chasing ghosts isn’t about catching them—it’s about understanding why we need to believe they might be worth the chase.

The Madrid Miners may never have played the Brooklyn Dodgers, but the story of that mythical game lives on, as persistent as desert wind, as enduring as the love between fathers and sons, as real as any truth that matters enough to keep telling. And sometimes, in the space between what we know and what we hope, we find exactly what we came looking for.

This is beautifully written, insightful, and deeply touching. Thank you for sharing yourself with us, Mike. Your writing is a gift🎁

P.S. I’d been totally game for running into a rattlesnake if I’d been there!

This was so beautiful...thank you for sharing it with us.